How One Man’s Suicide Changed Montana — and the National Guard

By Andrew Theen, Gulnaz Saiyed and Lauren Everitt Posted on February 14, 2012

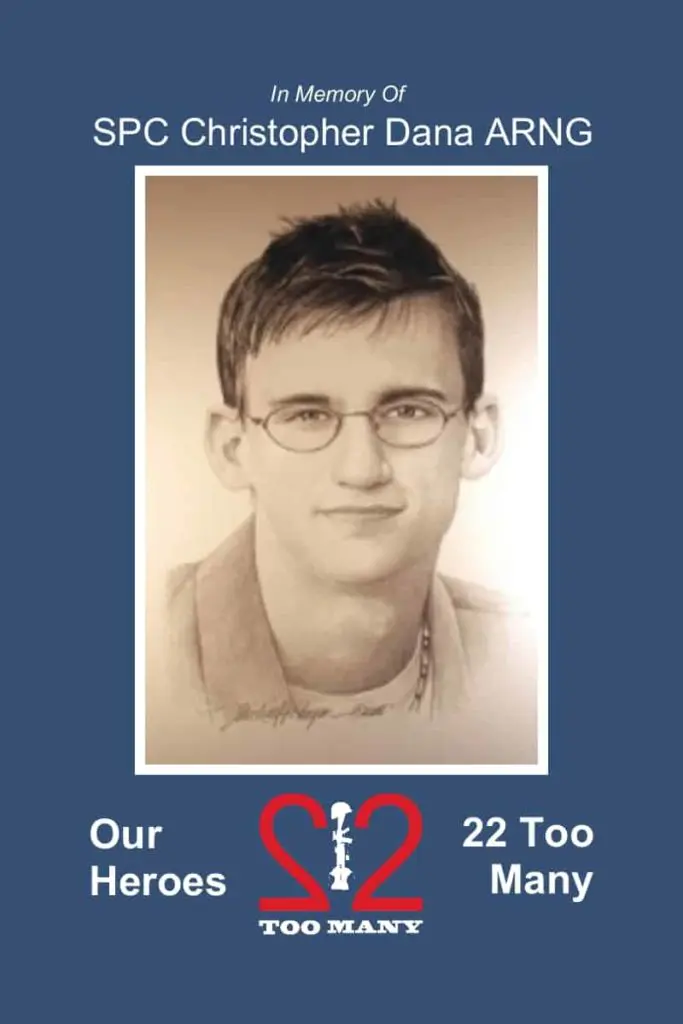

Chris Dana died by suicide in 2007 a year after deploying to Iraq with the Montana National Guard. His parents, Lisa Kuntz and Gary Dana, said he was a warm and loving young man, but the war changed him. (Andrew Theen/Medill)

HELENA, Mont. – Chris Dana joined the Montana National Guard as a senior in high school.

“He wanted to do something with his life,” Lisa Kuntz, his mother, said.

More than a year after graduating, in November 2004, Dana, a voracious reader and video gamer, went to Iraq as a gunner for Montana’s 1-163rd Infantry Battalion. He spent his deployment in Northern Iraq, often patrolling the notorious “Highway of Death” from behind the guns of a Humvee during the height of the insurgency.

Dana came back a year later a profoundly different man. He gradually isolated himself from friends and family, stopped showing up for work at Target, quit attending his mandatory National Guard drills and was less than honorably discharged.

On March 4, 2007, at age 23, leaving no note, he shot and killed himself in his room. His father, Gary Dana, found the crumpled discharge notice from two days earlier together with a receipt for .22 caliber rifle shells.

The suicide shocked the Montana National Guard. Although the guard was surpassing all requirements set by the Defense Department to assess and treat Montana service members as they came home, the state concluded four months after Dana’s suicide that it wasn’t doing enough for those with post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental health issues.

“We didn’t understand what post-traumatic stress disorder was. …We didn’t understand what caused it or anything about it, so we had to do what we could to learn about that,” said Col. Jeff Ireland, the Montana guard officer in charge of personnel at the time.

Dana’s death was the impetus for a task force that took a hard look at the post-deployment effort, especially the mental health screening process of returning Montana National Guardsmen and women. That investigation found Dana’s case wasn’t isolated, and that other returning service members were rushed through the same inadequate system and left with nowhere to turn.

“The fact is he was really seriously injured and nobody including myself understood the extent of the injury or really how to get him help,’ said Matt Kuntz, Dana’s stepbrother and executive director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness’ Montana chapter.

Kuntz’ advocacy on Dana’s behalf ultimately resulted in a national policy mandating confidential mental health screenings for all service members before they deploy and at regular intervals for up to two years after they come home.

Nearly five years after Dana’s death, the post-deployment process is radically different for members of the reserve component nationwide. They are now required by Congress to attend reintegration events 30, 60 and 90 days after returning from a deployment in addition to the demobilization process immediately after returning home.

The aftermath

Following Dana’s suicide, Kuntz, then a corporate lawyer, decided he had to do something. Older than Dana by seven years, he was angry that news reports focused solely on the suicide and not on the circumstances leading up to it. His family believes he suffered from undiagnosed PTSD.

Kuntz couldn’t escape the sense he hadn’t done enough to help Dana. Gary Dana, Chris’ father, had asked Kuntz to reach out to his increasingly isolated son over the holidays, but they failed to connect.

The solidly built and soft-spoken Kuntz thought he was the one who should have gone to war, but the West Point graduate was injured during Ranger school.

“I was a peacetime chump, and he’d done it. I was just really, really proud of how well he’d done and how brave and how well he’d served,” Kuntz said.

At the academy, he learned missions need a direct, tangible objective so he decided his campaign for better guard mental health treatment would focus on confidential, mandatory in-person mental health screenings. He believes this could have saved his stepbrother’s life. He targeted the commander of the Montana National Guard, Gov. Brian Schweitzer.

Kuntz wrote op-eds that appeared in papers across the state, with the governor’s phone number at the bottom. He rallied veterans groups and peace advocates to the cause.

A month after Dana’s death, Kuntz’ campaign had struck a chord. Maj. Gen. Randall Mosley, the Montana guard’s top officer, convened a task force of military and mental health experts and state legislators. Their assignment was to evaluate whether the care and support of returning guard members was adequate, including the federally mandated post-deployment health reassessment process.

The task force spent four months investigating, and in June 2007, sent a sharply critical report to Mosley that described systemic problems at every level of the post-deployment and reintegration effort.

“Painfully obvious…is that the citizen soldier, now a combat veteran, oftentimes needs services and support resources that extend far beyond what the Montana National Guard or the PDHRA (Post-Deployment Health Reassessment) program currently offer,” according to the report.

Montana’s commanders, service members and their families lacked the fundamental knowledge and training they needed to detect the early warning signs of PTSD, TBI and other combat-related stressors, according to the task force. It called for a statewide network of resources that would “meaningfully assist” veterans facing those issues.

The task force recommended 14 fundamental changes in how the Montana guard operated, including re-evaluating a policy that allowed guard members such as Dana to be less than honorably discharged because they repeatedly missed drills.

It also found widespread reluctance among guardsmen to seek mental health services and a lack of coordination among the Department of Veterans Affairs and local agencies. It said Dana’s experience was a “microcosm” for Montana veterans and reservists. Many were isolated by the vast geography of the state, far from “battle buddies’’ who shared the harrowing experiences of war with them

A broken system

When Dana returned from Iraq in November 2005, he considered his post-deployment health screening a joke, according to family members.

He didn’t think he had a problem.

Janna Sherrill, Dana’s stepsister and an occupational therapist, suggested he get help for what she suspected was PTSD. Dana, however, told her his difficulties getting back on track were no different than those of his fellow combat veterans.

His parents said their son’s experience as a gunner didn’t fit his quiet nature and took a heavy toll.

Meanwhile, Gary Dana received repeated calls from a guard commander in Butte demanding to know why Chris failed to show up for drills.

Lisa Kuntz said her son grew uncharacteristically cold and that his isolation deepened. Chris missed family events over the holidays and yelled at her when she showed up at his job, telling her to leave him alone.

The task force noted that Montana had followed established procedures by the book, but it wasn’t enough to catch Dana.

The report, and critics like Kuntz, said the system left too many outs, too many opportunities to avoid getting care. Symptoms of mental injuries can manifest months or years after combat. As a result, the task force recommended requiring returning troops to speak with a professional well after returning from war. Making it mandatory also would eliminate the stigma associated with seeking mental health care.

The task force also noted that the Army had implemented follow-up assessments in January 2006, and that the National Guard followed suit four months later. But it said the screenings, 90 and 180 days after returning from a deployment, weren’t always effective, confidential or administered by qualified professionals.

Eric Kettenring, a retired Army Reserve colonel and a VA mental health specialist, was struck by how few people understood what it meant to combat veterans and the mental health issues they experience.

One of the recommendations Kettenring advocated for as a task force member was for returning soldiers to quickly receive badges and awards they had earned. The report said delaying combat awards is demoralizing and affects qualification for some medical benefits.

Also significant, Kettenring said, the guard treated repeated absences from drills as delinquent behavior, as it did in Dana’s case, rather than as an indicator for depression, PTSD or TBI.

But, he said, “that’s what depressed people do. They don’t show up.”

An about-face

By January 2008, the Montana National Guard made all of the changes the task force had recommended.

Guard officials also looked to Minnesota, which began an innovative Yellow Ribbon Reintegration Program in 2005 that brought troops and their families together to address the challenges of reintegrating into civilian life.

Ireland customized the program for Montana, and went a step further. Knowing other states faced similar problems, Ireland made a CD with Montana’s reforms and sent it across the country.

Other states implemented some of the changes even though it wasn’t required.

“I think there’s a big fear in taking away states’ abilities to customize programs,” Ireland said.

Officials at the National Guard Bureau in Washington agreed.

Matt Kuntz’ commitment to mandatory confidential mental health screenings brought him to Washington, where he testified before Congress.

Sen. Max Baucus (D-Mont.) introduced legislation requiring the screenings in June 2009; it became law a few months later. Baucus called Kuntz “the real inspiration for getting this done.”

Back in Montana, Ireland and other guard officials continue to make sure mental health professionals screen returning service members. They also update the Yellow Ribbon program for families, with an emphasis on things “nobody wants to talk about” like suicide, anger and divorce.

Additionally, Montana has created crisis response teams made up of state behavioral health officers, chaplains and commanders.

“I don’t have any way to tell you that it’s saved one life, but I’m positive… that there are a lot of people that are alive because we have that,’’ Ireland said.

Last year, one of the state’s two teams responded to 63 crises for 41 individuals.

Since Dana’s death, the Montana National Guard has lost two more service members to suicide, both last year. Nationally, 2010 saw the most guard suicides since they began tracking them in 2007.

Dana’s father, Gary, said the awareness of mental health issues has increased dramatically since Chris’ death five years ago, and that the families of two other Montana veterans called him praising the new behavioral health center at the Helena VA. “It made me feel good that his death was a positive thing for people,” Dana said.

Dana’s mother, Lisa Kuntz, also said the changes enacted by Montana are heartening, as was the posthumous reversal of his less than honorable discharge.

“They did make some positive changes, very positive,’’ she said, “but it’s too bad that we had to lose our son for them to do that.”

http://nationalsecurityzone.medill.northwestern.edu/hiddensurge/how-one-mans-suicide-change-montant-and-the-national-guard/index.html