Soldier’s son on a mission to help others after father’s suicide

He has a message for other grieving military children

By Lindsay Wise / Houston Chronicle June 27, 2012

Timothy Swenson was 6 years old when his father, a soldier, died by suicide at Fort Hood. Thinking to spare the little boy, his mother told him that Daddy had died of a heart attack.

But Timothy’s grandparents, who had been taking care of him at their home in Humble, wanted to be as open as possible. They told him the truth.

“He didn’t believe us,” said his grandmother, Judi Swenson. “He said, ‘Nobody was in the apartment when he died. Nobody knows. I know he didn’t commit suicide.’ “

It took Timothy years to come to terms with how his father died. Now 13 and a student at Timberwood Middle School, he wants to help other grieving military kids heal.

“Let your feelings out. And just, like, don’t hide it,” Timothy advises. “Don’t keep it to yourself.”

For adults, he has this message: “Suicide is not the answer.”

Timothy’s father, Spc. David Paul Swenson Jr., served in the U.S. Army and Texas Army National Guard. He is among a record number of Guard members, reservists and active-duty service members who have killed themselves in the decade since the start of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Their children, like Timothy, grow up grappling with a complicated legacy of patriotism and pain.

“Timmy was extremely close to his daddy,” Judi said. “His daddy was his hero.”

‘Too much for him’

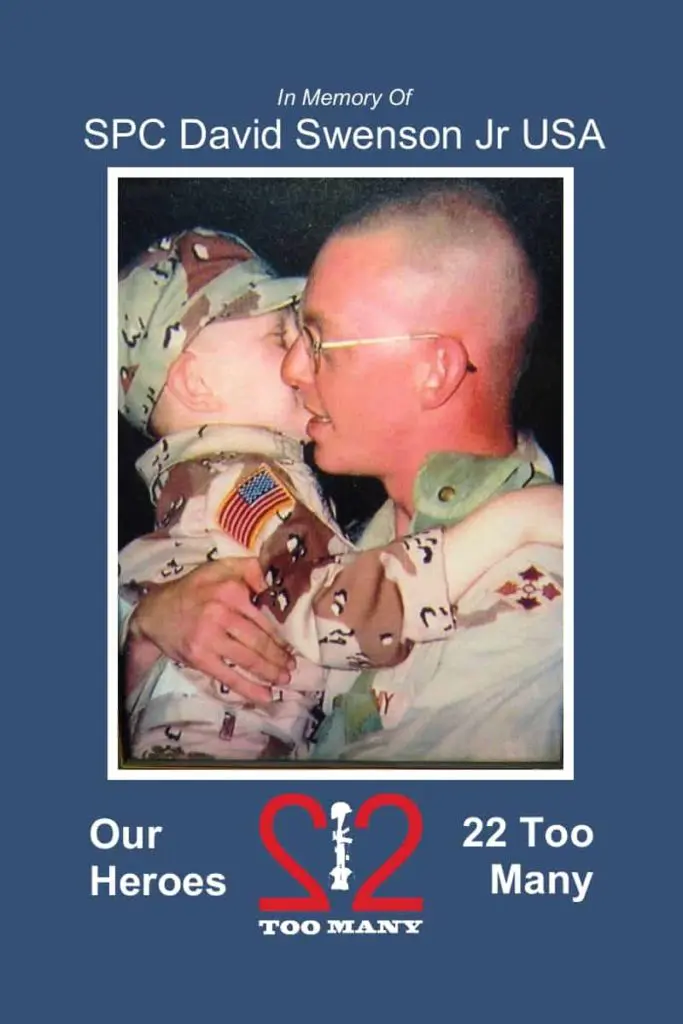

When his father returned from Iraq in 2004, Timothy came to the welcome-home ceremony dressed in a pint-sized soldier uniform.

“I can remember seeing him and telling him I missed him,” Timothy said.

A photograph of the reunion shows Timothy clutched in his father’s fierce embrace. It’s an iconic moment portrayed countless times on front pages and evening news shows across the country. But for the Swensons, David’s return from war was the beginning of their nightmare, not the end.

David had separated from Timothy’s mom, then broke up with a girlfriend. He struggled to pay his bills.

“He was drained emotionally. He was drained financially,” Judi said.

He also was distraught to learn he had been assigned to another unit and wouldn’t return to Iraq with his buddies when they deployed again.

“The Army and the deployments and stuff – that was his calling, that was his comfort zone,” Judi said. “Coming back and the stresses and the day-to-day life was too much for him.”

David died of a self- inflicted gunshot wound in Killeen on June 16, 2005. He was 26.

At the cemetery, Timothy walked behind his father’s caisson in the same uniform he’d worn to welcome him home.

“He was hysterical throughout the whole funeral,” Judi said. “Everybody kept saying he’s too young, he doesn’t understand.”

She knew it wasn’t going to be easy for Timothy, but decided it would be worse to lie to him.

Refused to believe

“He would have questions, and I wanted him to be comfortable always asking questions of me,” Judi said. She and her husband later adopted Timothy.

“The more honest, the better it is in the long run … he has to know that he can ask you something and believe what you tell him,” she said.

Judi tried to explain the tragedy in terms a 6-year-old could grasp. She told Timothy that a gunshot, not a heart attack, had killed his daddy. She said his daddy was stressed out and sad.

“His heart was broken, and his brain didn’t know how to handle it,” Judi told the boy.

Timothy couldn’t believe that the brave soldier he worshipped had shot himself on purpose.

“I thought that he was doing that thing where they have to spin their guns and stuff, like for a 21-gun salute, and that he accidently pulled the trigger,” Timothy said. “Or that he was cleaning his gun and it went off.”

It wasn’t until October 2009 that Timothy accepted what had happened.

His grandparents had taken him to California for the first military suicide seminar and Good Grief Camp organized by the nonprofit Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors. Participants were divided into age groups, and Timothy found himself seated at a table with kids who had gone through what he had.

“For a child to walk into a group setting and they’ve seen all these other kids who’ve had a similar experience to theirs, there’s a level of understanding that you just can’t find in any other environment,” said TAPS spokeswoman Ami Neiberger-Miller.

Reaching out to others

The TAPS community includes about 450 military children who are mourning a relative’s suicide, Neiberger-Miller said.

“Once I saw how many kids had dads who did it, I kind of realized it was suicide,” Timothy said.

“That’s when his grieving started all over again,” Judi said. Timothy said he was “angry, then sad.”

The other children in TAPS comforted him, he said. “They were just helping me, telling me the world wasn’t over,” he said.

Timothy now attends TAPS programs every year, all over the country.

“He goes to get his own good out of it and tell his own story, but a good portion of his benefit is reaching out to others, even though he’s still a kid,” Judi said.

Earlier this year, Timothy posted an essay about his father on the website of a fundraising walk for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

When his father was in Iraq, Timothy wrote, he worried every day that something might happen to him.

“When he came home safe, I was so happy to see him at the Ft. Hood welcome home ceremony,” he wrote. “I knew he would go back to the war some day, but I thought he would be safe while he was home.”

Timothy said he was walking to raise money for the foundation “so maybe someday, a kid’s dad will decide to live instead.”

————————————

Army Spc. David P. Swenson Jr. loved the Army, Swenson said, but had recently transferred to a new unit on Fort Hood, Texas, and sorely missed the battle buddies in his old one. He disappeared one night and his squad leader called Swenson to see if she could track him down. She found him at his sister-in-law’s house. He told his mother that he hadn’t slept in three days and wanted to return to his former unit so he could deploy with them in November.

Swenson spoke to him of his responsibilities and how important it was to fulfill them. “One of the hardest things — and there are many things that are hard — is my son begged me, ‘Please don’t make me go back,’ but we raised him to do what’s right,” she said, wiping away tears. “He had a job to do so I made him go back that night.”

The soldier drove back to post, took all of the decals off his truck so his father could have it, then called a close friend. He threatened to harm himself so his friend called the police. The police were enroute when Swenson’s son shot himself in the head.

He left a 6-year-old son, Timmy, behind. Swenson and her husband had been caring for him, and after their son’s death, worked to adopt him. The adoption was finalized last week, she said.

“I waited 10 years to have him,” Swenson said of her son. “I thought I’d never be a mom again, but now I’m a mom again. I’m joyous, but with a big cloud overhead.”

Timmy struggled for years with his father’s death, refusing to believe it was a suicide. “He didn’t think it was humanly possible for a parent to kill himself if they have children,” Swenson explained.

He finally accepted the truth while attending last year’s TAPS suicide survivor seminar in San Diego, she said.

“It hit him like a bucket of ice water,” Swenson said. “He came to the realization that maybe Daddy killed himself. TAPS got through to him and helped him through it.”

TAPS is their family now, she said.

SPC David P Swenson, Jr. Born 7/23/78 in Teheran, Iran. Died by suicide at Ft Hood, Tx 6/16/05. Active duty Army 4ID. Left parents and a 6 year old son, Timmy. We adopted Timmy in 2010. He is now 17.