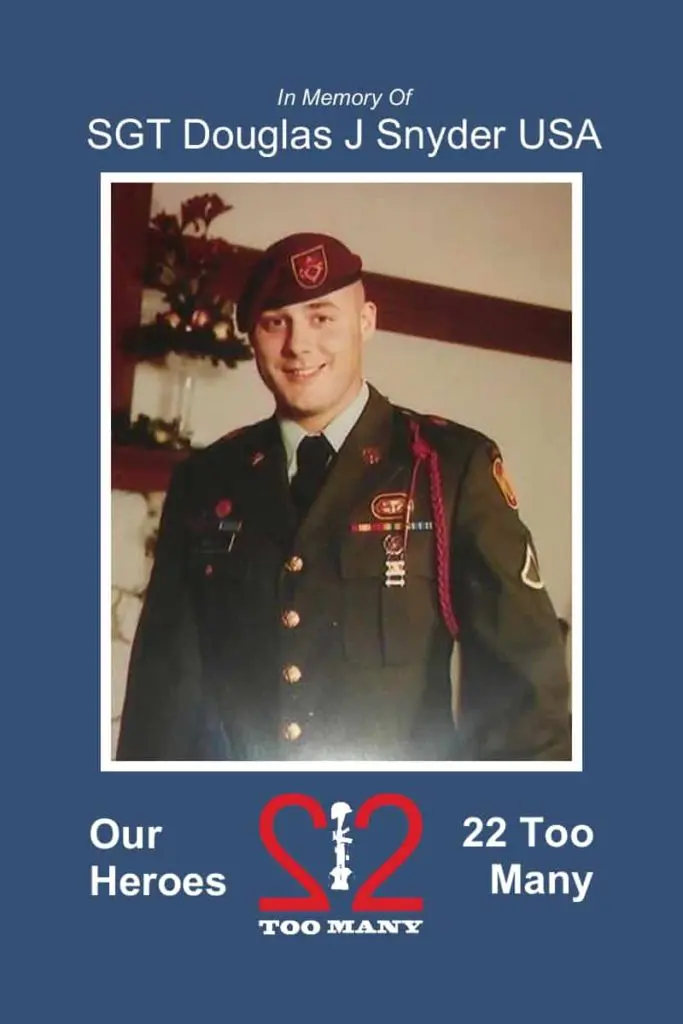

Beloved son and brother, Douglas James Snyder, 32, passed unexpectedly on Nov. 24, 2009.

Doug was born May 11, 1977, in Anderson. He is a graduate of Highland High School in Anderson and later joined the United States Army.

Doug served until 2004 as a field artillery crewman, as a member of the 82nd Airborne and performed two tours in Iraq: in 2002 at the start of “Shock and Awe” and redeployed in 2003.

“Douglas was diagnosed with PTSD/TBI and was arrested in 2009. He told the jailer he was a vet and was having blackouts. They demanded proof. The Houston VA sent a paper stating he never served in the military; as a result, he was informed that he was nothing but “a lying felon”. He hung himself a shortly thereafter. In reality, the VA didn’t take the time to look for his records, and it took us 3 1/2 hours to locate them the next day. I just recently asked for his medical records and was sent a disc clearly marked with his information. When I opened them up I realized the VA had sent me someone else’s information.”

From Indystar

Swarens: VA hospital’s tasteless email reignites mother’s grief

tim.swarens@indystar.com

Six years after, Marcia Snyder still mourns for the son she gave to her nation, the son who left Indiana to go to war. The son who came home a wounded, broken warrior.

The son who — struggling with a brain injury, post-traumatic stress, blackouts, homelessness, drug abuse and run-ins with police — used a blanket to fashion a noose in a Texas jail one day in 2009.

The son she buried. At the age of 32.

A fresh wave of grief and anger washed over Marcia Snyder this past week. “Total rage” is how she described her feelings to me.

The rage was set off by a story from my colleague Tony Cook, who uncovered an appalling email sent by a manager at the Roudebush Veterans Affairs Medical Centerin Indianapolis. The email, routed to other VA employees, included photos of a toy elf in a variety of tasteless poses.

In a caption to one photo, the elf is described as pleading for Xanax and “self-medicating for mental health issues.”

Marcia Snyder knows well the agony that pushes veterans to self-medicate. Her son, Doug, was prescribed as many as 15 medications at a time to treat Traumatic Brain Injury and PTSD.

But the pain, the fear and the flashbacks — the hellish aftermath of his years of fighting with the 82nd Airborne in Iraq — didn’t stop. And so he turned to illegal drugs in a desperate, futile pursuit of relief.

It’s a story all too familiar to Jim Bauerle.

A retired U.S. Army brigadier general from Carmel, Bauerle now serves with the Military/Veterans Coalition of Indiana, an umbrella organization of groups that assist veterans and active duty personnel across the state.

When I started to describe Doug Snyder’s story to Bauerle, he stopped me. Then proceeded to recite all the low points of the deceased sergeant’s agonizing journey.

It’s not that he knew or had ever heard of Snyder. It’s that Doug Snyder’s path of descent has been followed, before and after, by thousands of America’s warriors.

That descent all too often reaches a heartbreaking destination — an estimated 22 veterans a day from across the nation, like Doug Snyder, take their own lives. That equates to about 145 military suicides each year in Indiana.

No doubt many of those men and women, in various stages of desperation, tried to find help at the VA medical center in Indianapolis.

How to explain then why a manager at that hospital, a social worker no less, saw fit to send an email that included a photo of the elf hanging from a strand of Christmas lights. With the caption: “Caught in the act of suicidal behavior (trying to hang himself from an electrical cord).”

Apparently it was meant as a joke.

But no one is laughing. Certainly not Marcia Snyder.

“I know all about medical humor. I’m a registered nurse,” she said. “But there’s a line you draw.”

As outrageous as that email is, there’s an outrage that’s much, much worse — the shameful fact that we as Americans have so badly neglected our support systems for veterans.

The VA’s falsification of records, the low quality of care, the stumbling bureaucracy have been well-documented in recent years, and while promises to improve were made, and at some level honored, those in need of help, and those who love them, continue to raise alarms about the agency’s deep-seated problems.

Jim Bauerle and Monica Snyder — the general and the nurse — are among those sounding the alarm. One lost men on the battlefield. The other lost a son in the homeland. Both are heartbroken by what they seeing happening with veterans today.

“We’ve got a crisis on our hands in the state of Indiana and across the nation,” Bauerle said. “The VA and the federal government are just not taking care of the problem.”