The Endless After War

By Martin Kuz | San Antonio Express-News | Sunday, July 31, 2016

“He went to fight a war over there and then he came back and had to fight another war.”

Sara Mata has followed a morning ritual since marrying Manuel Garza five years ago. She pours two mugs of coffee and sits down beside him to talk about what’s on her mind, musing out loud about their children and families, about happy memories and dreams for the future.

Until last fall, the conversations took place at the kitchen table in their modest apartment on Laredo’s south side, the couple surrounded by the clutter of family life.

Now Mata sits at the foot of her husband’s grave in a city cemetery, shadowed by the anguish of loss. She talks to the white marble headstone that identifies him as an Army veteran who served in the Iraq War. She stays long enough that his coffee turns cold.

“There are so many unanswered questions, so many things I would like to know,” she said. “I ask him when I come here.”

Garza shared little with Mata about the causes of the war within him before his death Sept. 18, when he jumped from a freeway overpass on the city’s northern edge. He clutched two yellow blankets that belonged to his young daughter as he fell to earth.

Mata knew only that he had received a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder linked to his two combat tours in Iraq. The second ended in 2005, a full decade before his suicide at age 33, and six years before they began dating.

The passage of so much time illuminates the long reach of PTSD and the enduring, largely invisible aftermath of America’s 21st-century wars on veterans and their families. Their plight deepens in the border region of South Texas, where the Veterans Affairs health care system lacks a full-service hospital and few behavioral health clinics exist in the private sector.

The VA released a report earlier this month that shows the suicide rate for veterans nationwide has surged 32 percent since 2001, compared with 23 percent for civilians. Much of the increase occurred among veterans under age 40.

The civilian suicide rate was 13 deaths per 100,000 people in 2014. Veterans age 18 to 29 were almost six times as likely to end their own lives, and the rate for those age 30 to 39 more than tripled that of civilians.

An estimated 13 percent to 20 percent of the 2.6 million veterans who deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan returned with PTSD. The vast majority recover from or learn to tame symptoms that include acute anxiety, anger, flashbacks, insomnia and hypervigilance, a nearly constant state of intense alertness.

But combat trauma traces a jagged trajectory, and symptoms can linger or resurface even decades later. A veteran’s choice to cope in silence can sow confusion among family members exposed to behavior that appears erratic and inexplicable.

Garza’s desire to shield Mata from his inner turbulence typifies the reluctance of veterans, hewing to the military ethos of self-reliance, to open up to loved ones. The blurred reasons behind his decision to kill himself contrast with the painful clarity of his absence.

“He went to go fight a war over there, then he came back and had to fight another war,” said Mata, 32, the mother of four children, the youngest two with Garza. “And now he’s gone and we’re fighting his war.”

A previous VA study showed that the veteran suicide rate runs sharply higher in less populated areas compared to urban centers. More obstacles to VA and private care, coupled with pervasive skepticism about mental health treatment, plague veterans in outlying regions.

Gabriel Lopez, founder of the South Texas Afghanistan and Iraq Veterans Association based in Laredo, established the group, in part, to aid former service members struggling with combat trauma.

Lopez describes veterans lost to suicide and their surviving family members as uncounted casualties of war. He has consoled Mata and other spouses of veterans who took their own lives, and motivated by their grief, he seeks to disabuse veterans in crisis of the corrosive belief that suicide will relieve their families of a burden.

“We veterans are very good at hiding things emotionally,” he said. “That can be useful in a lot of situations. But the problem with suicide is, you can’t come back to life and see what you’ve done.”

Garza and Mata belonged to the same large circle of friends in Laredo but had talked only in passing. One day in 2011, after she accepted his friend request on Facebook, he called her.

“Can I talk to Maddilynn?” Garza asked.

Stunned for a moment, Mata laughed and handed the phone to her 4-year-old daughter.

Garza invited her out for ice cream, and when Mata took the phone back, he said in a playful tone, “You can come along, too, if you want.”

The lopsided double date foretold four years of family happiness for Garza and Mata. They married later that year, and their household grew as they added a daughter and son, Melanie and Manuel Jr., to Mata’s two oldest children, Maddilynn and Jeremiah.

Burly and bald, with a dark beard and shining brown eyes, Garza brought a boyish spirit to fatherhood, swaddling the family in his banter and big laugh.

He joined the kids in break-dancing, playing video games and roasting marshmallows for s’mores. When Mata arrived home after picking them up from daycare and school, he waited on the front steps of their apartment to trade hugs, high-fives and goofy faces.

The couple liked to take their brood fishing at Lake Casa Blanca, and as he helped the children cast their lines and reel in catfish and bass, Mata wondered at her good fortune.

“The way he treated my kids made me fall in love with him. He never wanted to do anything alone. He was so devoted to his family and treated me like a queen,” she said. “He was the man I thought I was never going to meet.”

Garza pushed Mata to earn her GED and attend college to pursue a degree in social work while he handled more of the parenting duties. He had quit a pair of tedious jobs to enroll in classes in computer science, and the couple planned to move this year so that he could complete his coursework at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

He supported the family largely with his monthly $1,200 disability payment from the VA. After his honorable discharge from the Army in 2007, the former sergeant had received a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder related to his two tours in Iraq.

Garza never discussed the war with Mata or the experiences that caused his condition, and he showed a similar reticence about recalling any aspect of his seven-year military career.

He allowed the children to wear his Army medals and pin them on stuffed animals. When Mata praised him as a war hero, he replied with a grimace and switched the topic.

She knew he subdued his sporadic insomnia by walking the boundary of their apartment complex, as if he were patrolling the perimeter of a military base.

Nightmares sometimes ruptured his sleep, and she hugged him close when he awoke crying or shouting. He forgot the episodes by morning, and when she told him what happened, he reassured her that nothing was wrong.

Following his cue, she held back her questions about Iraq and PTSD, soothed by his mostly untroubled manner, and unaware of the latent threat that combat trauma can pose.

In the last year of his life, Garza remained carefree around the children, whether on road trips to South Padre or barbecuing their catch of the day on the grill outside the apartment.

But Mata noticed changes. He drank and smoked more, and his insomnia and nightmares occurred with greater frequency. He suffered from panic attacks and brief periods of depression, and he developed bowel incontinence, a symptom of PTSD typically induced by anxiety.

Since leaving the military, Garza had attended occasional counseling sessions with VA therapists in Laredo, Harlingen and Corpus Christi.

Last September, a week before his suicide, he received a referral from a Laredo provider to see a VA psychiatrist in San Antonio. He alluded to concerns about his self-control to Mata without elaborating.

The number of former service members seeking behavioral health care through the VA soared from 925,000 in 2006 to 1.6 million last year. The rising demand prevents clinicians from counseling most veterans more than once every few months.

Gabriel Lopez, founder of the South Texas Afghanistan and Iraq Veterans Association, regards the growing need as the unseen legacy of America’s distant conflicts.

“This is war coming home,” said Lopez, 48, a Navy veteran who has been diagnosed with PTSD linked to his tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. “This is the price we’re going to have to pay for the fact that we’re always at war. It’s not going to end.”

In some cases, VA providers in the South Texas border region send patients to larger networks in San Antonio and Houston to reduce the wait for an appointment. The referrals require veterans to travel long distances to meet with unfamiliar clinicians.

Mata supported Garza’s decision to make the trip to the VA hospital in San Antonio. She joined him for the drive and they brought Melanie, their 2-year-old daughter, who slept in the back seat nestled in a pair of yellow blankets.

The VA visit marked the beginning of her husband’s final 48 hours. In Mata’s version of events, after meeting with the clinician, he became lost within himself.

Garza withheld details about the session from her beyond claiming that the psychiatrist appeared indifferent to his condition and told him, “It’s all in your head.”

Federal policy prohibits VA officials from commenting on the care of individual veterans. For Mata, proof of the session’s effect emerged in the ensuing hours as Garza, his mood darkening, spiraled out of reach.

The couple stayed with her brother in San Antonio overnight. Garza retreated into his mind and slept little, if at all. The next morning, during the trip back to Laredo, he alternated between stretches of silence and talking in a voice flat and faraway.

In the late afternoon, after returning from a short visit with neighbors, Garza left the apartment, telling Mata he wanted to buy beer. An hour or more had passed when he called her.

Caught between anger and unease, she demanded to know where he had gone.

He asked to talk to the children. She repeated her demand. They went around several more times before he relented.

“Just tell the kids I love them,” he said.

He sounded weary, broken. Her thoughts fogging with dread, she shouted at him in desperation.

“Come back and tell me and tell our kids!”

“I love you. I love them.”

Mata heard nothing more from him. She waited on the front steps through the night, walking inside at 7 a.m.

An hour later, she answered a knock at the door. Two police officers stood before her.

Sara Mata sat in the Chevrolet Yukon guessing at her husband’s last thoughts. A few days earlier, in the predawn hours of Sept. 18, Manuel Garza had parked the aging SUV on the shoulder of a highway overpass in Laredo.

He stepped from the truck carrying two yellow blankets that had been wrapped around his young daughter during a trip to San Antonio less than 48 hours earlier. He and Mata had traveled to the city for his meeting with a VA psychiatrist, and not long after they returned home the next day, he went out and never came back.

The sun had yet to rise. He moved closer to the concrete wall of the overpass. His feet left the ground.

Mata retrieved the truck from a police impound lot. She climbed behind the steering wheel, and when she could breathe again, she asked him question after question, trying to make sense of what he had done, searching for answers that still elude her almost a year later.

“For someone like him to suddenly take his own life — I think that’s what you can’t understand,” she said.

His suicide has given Mata an unwanted education in post-traumatic stress disorder. She has read books and watched documentaries on the subject, and enlightened by the stories of other combat veterans, she has formed theories about his behavior.

She thinks it’s possible that he started drinking more to stifle memories from Iraq. He may have preferred shopping for groceries late at night to stay away from crowds that could trigger his anxiety. Perhaps he imagined himself a threat to or a weight on his family and believed his death would spare them suffering.

Mata heard from a friend of Garza’s, another Iraq War veteran, after his suicide. He told her that Garza avoided talking about the war to shield her from his trauma. She laments that she has come to recognize the contours of PTSD only in the wake of his death.

“If I had known more, I would have tried to get him help,” she said. “If he had opened up to me a little more, maybe he wouldn’t have felt the way he did.”

His absence is a constant presence as she strains to raise four young children on her own.

Maddilynn sleeps in his Tennessee Titans jersey. Jeremiah wears his watch, Melanie keeps his wallet. When the family nears home while riding in the Yukon, Manuel Jr., too young to realize the truth, raises his arms and shrieks, “Yay, daddy!”

Mata hides her panic attacks and tears from them. She withdraws to the bedroom and shuts the door. She steps into the closet and presses her face against his shirts to breathe him in, or draws a bath and pours a few drops of his shampoo to feel him around her.

His spirit embraces them. They talk about him, repeat his jokes, invoke him in their prayers. She brings the kids to the cemetery once or twice a week to spend time at what they call “daddy’s house.”

Most days she visits the grave alone. She brings two mugs of coffee and sits down. Her long, dark hair grazes the earth, her brown eyes cloud with tears.

She talks about the kids and her parents and anything else on her mind. She tells him that she loves him and misses him and needs him.

She knows he will never return from war. She will never stop waiting.

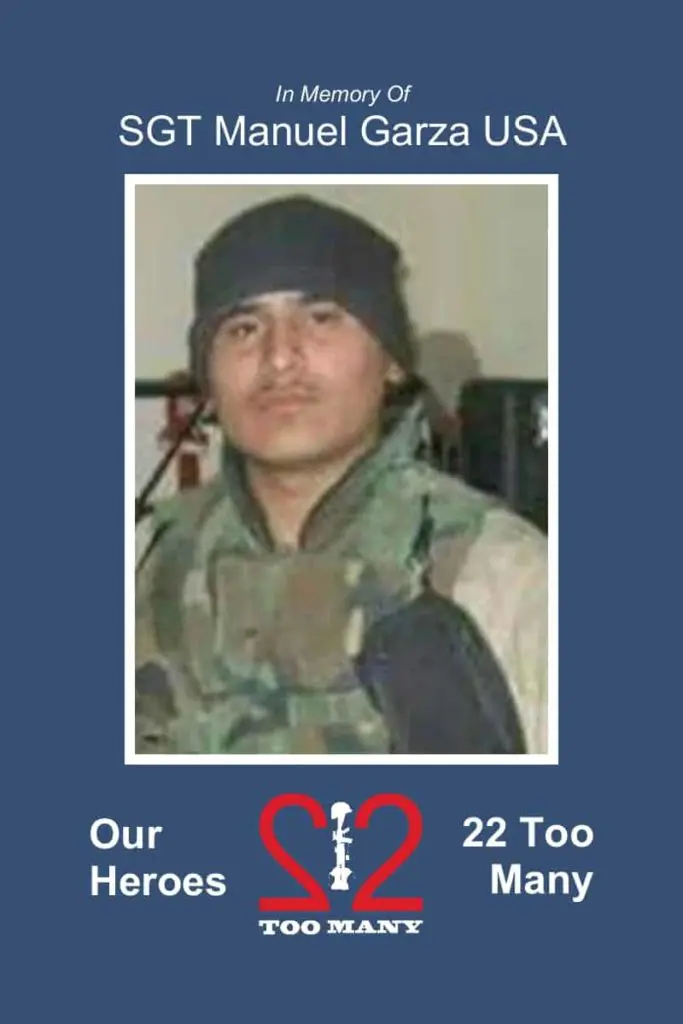

#22TooMany#OurHeroes are #NeverForgotten