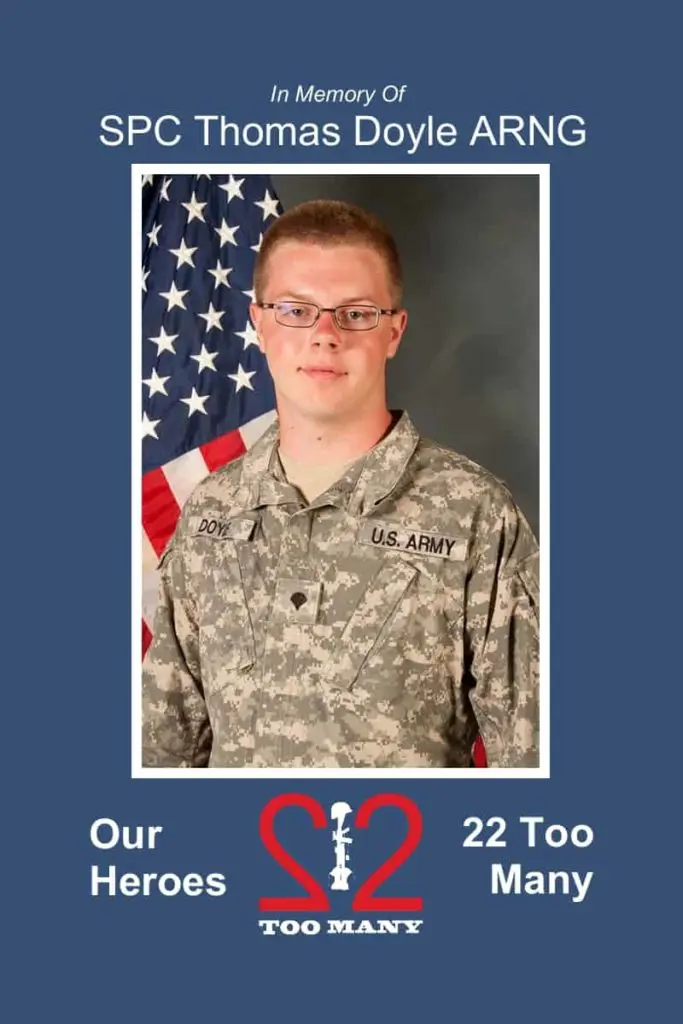

“Silence the Stigma” 2nd Annual Ride in conjunction with the American Foundation of Suicide Prevention. Jamestown, ND on July 19, 2015. ‘We will be hosting this ride for the 22+ and others we have lost. We started this ride in memory of my son, SPC Thomas Avery Doyle, who was lost to PTS and suicide.’

Speaking out for Tom: After losing soldier son to suicide, Jamestown family seeks to dispel stigmas

By: Ryan Johnson, Forum News Service

JAMESTOWN, N.D. Beth Doyle-Lautt has gotten used to the clutter in her house. A basement room is filled with boxes and totes, tools and extra furniture. A basement room is filled with boxes and totes, tools and extra furniture.

The shed her husband, Dave Lautt, bought to store his new Harley-Davidson in last year is too full for the motorcycle, which now stands in the garage that doesn’t have room for their pickup.

“It’s too soon to get rid of anything and too soon to even go through it yet,” he said. “We will; we’ll get there. It’s just on our terms.”

Since Sept. 7, 2013, it’s been easier to keep busy than dwell on the loss they suffered that day when their son, Thomas Avery Doyle, a specialist in the North Dakota National Guard who served in Kuwait, died by suicide at the age of 22.

The couple have since worked to break through the stigma surrounding mental illness and post-traumatic stress disorder within the military and the world at large – something they believe contributed to their son’s suffering and eventual death.

They’ll participate in the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention’s Out of the Darkness annual community walk at 2 p.m. today in Fargo’s Lindenwood Park, as well as in the foundation’s walk in at 10 a.m. next Saturday in Jamestown.

They don’t like talking about it, which brings back painful memories and the what-ifs that have haunted their thoughts. But after Tom lost his voice, his parents are finding theirs, and they won’t be quiet about it.

“We’d walk a million miles if it would bring Tom back,” Doyle-Lautt said.

“We will anyway, just to get the word out there,” Lautt added.

A NATIONAL FOCUS

Since 2003, the North Dakota National Guard has lost 16 soldiers to suicide: 15 in the Army National Guard and one in the Air National Guard. Fourteen were killed in action during that time, according to Chief Warrant Officer 4 Shelly Sizer, the state’s resilience, risk reduction and suicide prevention manager.

Across the country, the National Guard had the highest suicide rate of any branch of the military in 2012 with 28.1 per 100,000 members. America’s overall suicide rate was 12.3 per 100,000 people in 2011, the latest figures available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Among the National Guard, Reserves and four active service branches, there were 522 suicide deaths in 2012, according to the Department of Defense’s Suicide Event Report program, which has tracked the figures since 2008. Last year, 479 soldiers died by suicide.

Those figures don’t include veterans who die by suicide – an average of 22 per day, according to a 2013 Department of Veterans Affairs report.

The Department of Defense established the Defense Suicide Prevention Office in November 2011 to look into the issue in all branches of the military. Jackie Garrick, acting director of the office, said an overarching effort was needed to begin to understand what the data show, what programs already are in place and what else can be done.

“It really needed this centralization and standardization to really start to coordinate and collaborate on messaging, and to give it the teeth that it needed to bring the awareness to our senior leaders and really involve them,” she said.

The national data have helped leaders target relationship, financial, legal and mental health issues that could contribute to suicidal thoughts, she said, and the military has taken a more proactive approach, giving commanders and soldiers alike training on how to be resilient despite difficult challenges.

New confidential hotlines and services also help, Garrick said, because it reduces the stigma and makes it easier to ask for help – something she said should be seen as a sign of strength, not weakness.

“What we do know is that if you don’t ask for help and you don’t identify these problems, these problems only become worse,” she said. “It’s better to get to the problem and to ask for the help early, rather than wait when things do snowball.”

SERVING HIS COUNTRY

Tom Doyle was born Feb. 16, 1991, in Danville, Va., and moved to Jamestown with his mom 10 months later. Lautt started dating Tom’s mother in 1999, and quickly became a best friend and stepfather to the boy.

A hard worker who liked cars and girls, Tom wasn’t a joiner and didn’t get involved with groups or teams. But in 2008, he convinced his parents to let him enlist in the National Guard at the age of 17.

“He wanted discipline, and he wanted to serve people,” Doyle-Lautt said. “He told us once that if he went as a single guy, he could keep a father home with his children.”

Tom told the recruiter he struggled with depression when he was younger, though it seemed that battle was a thing of the past after he found treatment that worked and didn’t suffered from it in years.

Doyle-Lautt and Lautt say they made it a point to be open and honest with Tom and their five other children about their feelings and thoughts, and Tom reciprocated, keeping his parents informed about his own challenges.

Nearly four years after entering the National Guard, he heard the 188th Engineer Company would be deployed to Kuwait, and transferred from his own unit so he could serve beginning in October 2011.

Tom didn’t encounter much “drama” while in Kuwait, Lautt said. But he worried about his unit being deployed to Afghanistan, and told his parents about the traumatic training he went through while overseas.

He also expressed a futility about his role, Doyle-Lautt said, because he was a carpenter, not a soldier on the front lines.

Tom returned home in August 2012 with PTSD and an alcohol problem, something he said made it easier to “turn things off.” Just two days after getting back, he packed up and moved to Wahpeton to study construction management at the North Dakota State College of Science.

After driving home drunk one weekend, his parents took him to the emergency room, and he was eventually able to get help and kick his drinking problem. He told them he was also getting treatment for his PTSD.

Things were promising for Tom, Doyle-Lautt said. He started his own contracting company in Wahpeton, in addition to his other construction job, dated a supportive girlfriend and rented a house in Jamestown.

Doyle-Lautt talked with her son on Sept. 7, 2013; he told her everything was fine. He mentioned a problem he had during his National Guard drills that weekend in Wahpeton, saying he felt disrespected when somebody called him out in front of the unit. But it was a minor problem that was resolved, he reassured her.

The next morning, a police officer knocked on their door in Jamestown. Tom had died in Wahpeton sometime after the call.

PREVENTING MORE LOSSES

Lt. Col. Paul Harron, director of personnel for the North Dakota National Guard, said the military at large has made “great progress” in raising awareness about suicide and mental illness in recent decades.

Within the state, soldiers now have access to social workers, chaplains, human resource counselors and a psychological health coordinator to get help and get connected to the right resources and specialists.

While some of these efforts have been in place for years – licensed social workers have been on staff for more than a decade – some initiatives are more recent, Harron said, and are a result of leaders becoming aware of problems and shortfalls.

Soldiers now complete annual training that aims to teach resilience and coping strategies, for example. Newer resources, including a smartphone app that can help those in need find resources or get emergency help, are now being promoted, too.

“Any time we lose a soldier to suicide, that is like losing a member of our family,” Harron said. “We are doing everything humanly possible to prevent suicide within our ranks.”

Even while still coming to terms with their loss, Tom’s parents started to get involved in raising awareness and trying to prevent more families from experiencing the grief that has gripped their lives since they lost their son

They participated in the Out of the Darkness walk in Fargo last fall, and Lautt helped organize Jamestown’s first Ride to Silence the Stigma motorcycle run this summer.

It won’t change what happened to Tom, something they know all too well.

Still, they want to help cut through the stigma surrounding PTSD, mental illness and suicide that made their son afraid to talk about his feelings with friends and co-workers.

They think of it as giving back to the other soldiers and veterans who served their country, sometimes dying in the process.

And, it’s become a way of remembering Tom for the man he was, not how he died – a loving, “generous to a fault” kind of person who always wanted to make people feel loved and accepted, even if he couldn’t do that for himself.

“He was there for anybody in their time of need, but he never showed anybody his times of need,” Lautt said.