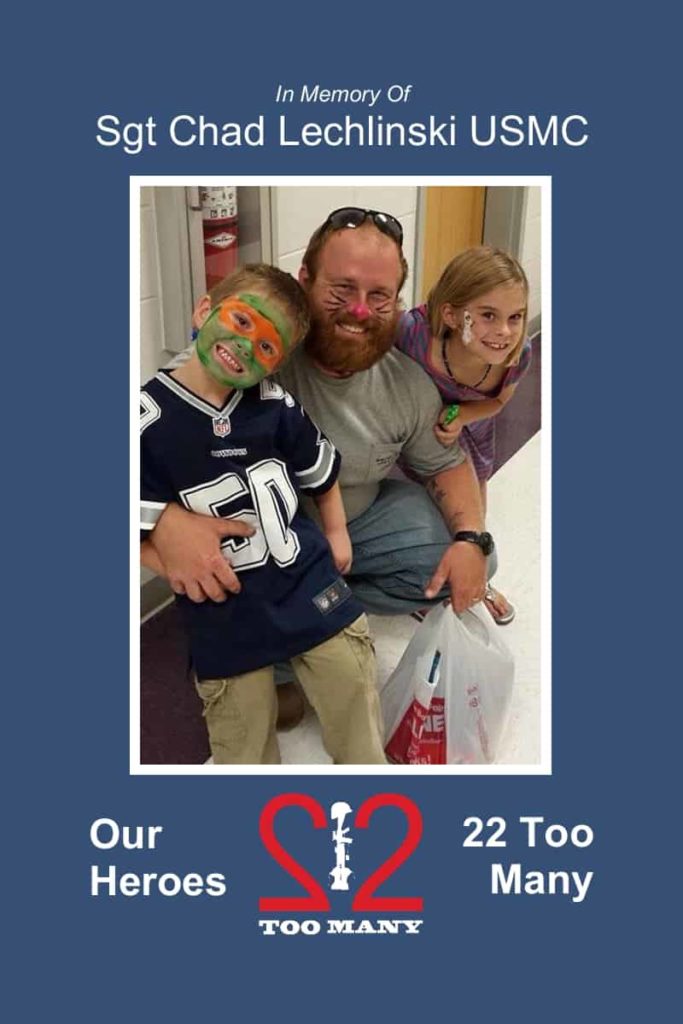

“Chad’s hobbies were fishing and hunting and spending time with his family – he was so in love with his wife and he loved his two kids dearly, but he just couldn’t take the demons in his head that the PTSD caused, along with the TBI.”

‘Jerome will be remembered by his family and friends as a faithful father, loving son, devoted friend, patriot and outdoor sportsman. Jerome was medically retired from the United States Marine Corps with eight years of service. His life and service to his family, country and friends will never be forgotten.’

“Widow Recounts Husband’s Stateside Struggles”

Jerome “Chad” Lechlinski took his own life on June 4 in his Jacksonville home. His widow hopes sharing his story will help others.

By Bianca Strzalkowski From JDNews.com

A Jacksonville man is one of the latest casualties of war, but his death did not occur in the foreign lands of Iraq or Afghanistan — his battle was lost at home.

Jerome “Chad” Lechlinski was a jokester, his wife Heather says, always looking for a way to make people laugh. On the inside though, Chad was fighting an internal enemy that not even his family fully realized.

Chad took his own life on June 4 in his Jacksonville home.

His widow hopes sharing his story will help others.

The 31-year old graduated from Dixon High School in 2002. He joined the Marine Corps to follow in his family’s long lineage of military service. In 2004, Heather and Chad Lechlinski met online while he was deployed to Cuba.

His wife had little familiarity with the military, but she moved to Onslow County to be with him and his family. His career in the infantry never slowed with continuous deployments to Africa and Iraq. During his first Iraq deployment in 2005, a suicide bomber attacked the vehicle Chad was driving, causing the death of one of his gunners. That incident was the start of something changing within him.

“He had a hard, hard time when he got back. He blamed himself since he was the one driving the Humvee, he felt like it was his fault,” Heather said. “No matter how many times we told him it wasn’t his fault, no matter how much time you have to heal, you can never get over seeing your friend pass away right next to you.”

Her husband was overcome by survivor’s guilt.

He returned from that deployment in August 2005 and by July of the next year the military slated him to go back to Iraq. Heather said she and his mother tried to fight it because they knew he wasn’t “up to par, he was still on light duty.”

“There was no reason he should have been deployed, we just weren’t getting the answers that we wanted or needed,” Heather said. “I think basically it was slap a Band-Aid on it and then send them back in.”

During the second deployment, Chad expressed a different demeanor to his wife. He had a fear within him, admitting he was scared and felt “less invincible” than he had before the tragedy that took his friend. By now, they had welcomed their first child — a daughter. Chad was injured again in Iraq and was returned home because of those injuries. His enlistment was up and after eight years in the Marine Corps, he left the military only to enter the complicated system of Veterans Affairs (VA).

Heather said she had little knowledge of what signs were associated with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). As a caregiver, a 1-800 number was constantly tossed at her. In the thick of it, sitting on the phone as her husband expressed suicidal ideations didn’t help their situation, she said. Fliers and brochures didn’t either.

“Nobody ever talks to you about it; nobody pulls you to the side and says, ‘Here, this is what might happen.’ So you’re really going into it blind,” she said.

Reflecting back, she says there were signs: emotions he displayed that she hopes by sharing can help other caregivers recognize what is happening before it is too late. He had sadness, crying, his appearance changed and there was a deep survivor’s remorse especially around the anniversary of the incident that claimed his friend’s life, she said. He would have little breakdowns where he would be emotional for no reason, and before his death, the episodes increased.

She also said Chad’s inability to get a continuum of care from the VA magnified his desperation. He was diagnosed with both traumatic brain injury and PTSD. Heather said he was given excessive medications to mask his symptoms but limited access to group therapies that would have him connected him to others feeling the same way. The meetings, she added, were often canceled.

She pleaded with her husband on the day of his death to please stay, expressing to him how much she and their two children, ages five and 9, needed him. The only source of comfort for her in the weeks since he died is to know he is no longer hurting.

“He was so full of life and at the end he wasn’t the happy-go lucky man that I married. (The only comfort is) knowing he’s not suffering anymore, knowing he doesn’t have to battle those demons that just ultimately took his life. He couldn’t handle it,” she said. “Never in a million years would I have imagined this would happen.”

If there is one piece of advice that Heather could pass on to other military caregivers, it is to not wait on the VA for care. She says seek your own doctor, even if that means incurring out-of-pocket expenses, because ultimately that could mean the difference in saving a veteran’s life.

The VA declined to comment on Chad Lechlinski’s case citing HIPAA and privacy concerns. Jeffrey Melvin, public affairs officer for the Fayetteville VAMC, provided the following statement: “Every Veteran’s death, especially at a young age, is a terrific loss. Our hearts go out to the Veteran’s family. Patient privacy laws will not allow us to comment specifically on this Veteran’s care.”

Melvin added that the local Jacksonville Community-Based Outpatient Clinic (CBOC) offers group and individual psychotherapy services. If veterans are unable to get an appointment for immediate care, they can seek a referral from their doctor to go to a non-VA provider.

A fundraiser has been setup for the Lechlinski family. Jennifer Burgess, Heather’s cousin, started a GoFundMe account for the family because Chad did not have a life insurance policy.

“My hope for her and the children is that on a day-to-day basis this will get easier and they will learn to deal with his loss because it was so sudden and unexpected,” Burgess, a Jacksonville resident, said. “I would like her story to get out there and make (people) aware they (veterans) mask the pain under the smile.”

For anyone interested in helping the Lechlinski family, donations are being accepted through the end of July at gofundme.com/Helpforheathef.

Veterans Affairs provided a list of resources for veterans and caregivers:

National Suicide Prevention Line 800-273-8255; press 1 to be routed to the Veterans Crisis Line.

Jacksonville Vet Center, 110A Branchwood Drive in Jacksonville; 910-577-1100 or 877-927-8387 (open to veterans who served in a combat zone or experienced military sexual trauma).

National Alliance for the Mentally Ill’s (NAMI) Coastal Division is specifically for families and loved ones caring for people recovering from PTSD and other mental health related issues. Contact number: 252-354-4722.

VA’s mental health website: mentalhealth.va.gov.