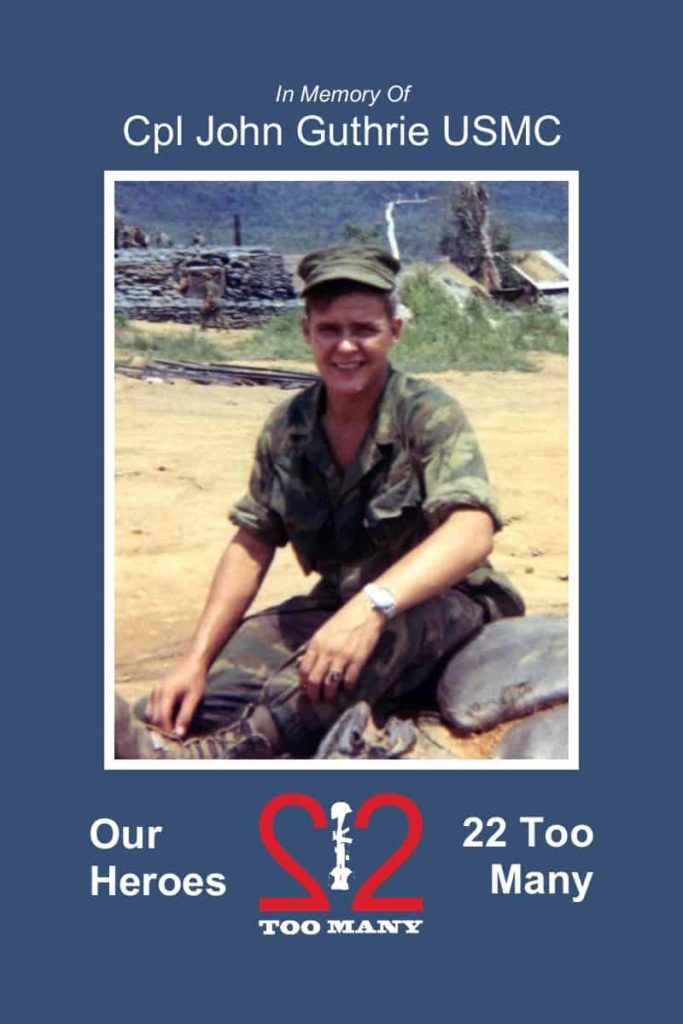

My father, affectionally known as John Boy, was a man’s man. Born in 1949, he hailed from the mountains of Asheville, NC and was the middle son of four brothers and two sisters.

Growing up in the early 50’s was a tough time for many families, especially in the wilds of western NC. My dad talked of a childhood living on dirt floors, an outhouse, no running water, but with an endless wilderness to hunt and fish. There was family lore, too. His father, my grandfather, Andrew Guthrie, used to run moonshine for a mob crime syndicate. Andrew lost his life early in a shootout in Detroit and left my dad’s mother no choice but to turn her children over to the Presbyterian Home for Children in Asheville. It was there that six-year old John Boy grew up until he joined the Marines at 18.

Growing up in an “orphanage” wasn’t like Orphan Annie and Miss Hannigan. My father vividly recalled the structure, discipline, and lifelong relationships he established. He felt it ultimately prepared him for the Marines. Even “old man” McKenzie, the school superintendent, became a mentor and much-needed father figure to my dad. There were fun times, too – shooting out red lights with guns, raiding storage sheds containing alcohol on the grounds of the Biltmore Estate, getting in epic fist fights with the rich kids across town. Teenage life wasn’t bad at all.

When my father graduated high school in 1967, he learned that his life-long friend had died in combat in some tiny, remote, alien place called Vietnam. Affectionally known as Viet-fucking-nam. John Boy decided, like a lot of white, southern, God-fearing boys in the late 60s, that he would join the Marines. In hindsight, it might not have even been a choice. It might have been destiny.

Life in basic training was a lot like life in the orphanage – Spartan, no privacy, everything shared – and every detail of your life known almost immediately by everyone around you. He excelled during the training and landed in Vietnam to fight Victor Charlie in October of ’68. Not yet 19, he was eager to fight for American freedom.

John Boy wasn’t very tall but he was a wiry, muscular, combat grunt. In fact, when I was 12, I already towered above him thanks to my mom’s side of the family. Given his height, his commanders knew exactly what job they had in store for John Boy. A .45 and a red capped flash light was all he needed. His job – to duck into the labyrinths of unending Vietnamese tunnels, locate Dogface Charlie, and eliminate him from the world.

I went caving once in Boy Scouts. A simple exercise where we found a hole in a barren cow pasture. Single file, we would enter the hole, turn on our overhead flashlights, and slink our way like inchworms down this narrow “tube” of dirt, grime, and mud. Ten feet inside felt like ten miles. My fear became sheer panic. It felt like the walls were closing in on me. I started hyperventilating, knowing that at any second there could be a collapse and instant death. I fought through my claustrophobia, came out into this cavern where we turned off our lights, and was met by instant night. Nothing, nada, zip – coffin blackness.

I shudder at what experiences John Boy must have endured, what he went through, what he faced. He never spoke one word about it.

After Vietnam, John Boy returned home. He was combat wounded, the “million dollar wound” which was a clean shot through the knee, and got a one-way ticket back to the world. He moved in with his brother, landed a job in Richmond, VA, and one night, ended up on a blind date where he met my mother. All of a sudden, life took an unexpected turn for John Boy. He had responsibilities of a different sort – a wife, a house, and a blue eyed baby boy – yours truly.

My mother would often describe John Boy as a deliberate man, a man who would sit back, smoke his Marlboro Reds and quietly assess the world around him. But his temper would snap with lightning speed, as if the dam within him was unable to contain the pressure of the turbulent thoughts and fears inside. When angered, he would be up and after someone in the blink of an eye.

One night, he foiled two men trying to break into our house. He was on the night shift, came home at 2am, and caught the would-be burglars red handed. He nearly ran one of them over with the car, and chased the other on foot. The police caught them. One of them bloodied and bruised. They went to prison.

John Boy was not the best of husbands in terms of patience, understanding, and nurturing. But John Boy was as reliable as they came. Helped neighbors without question, gave you the shirt off his back, stopped to help a complete stranger on the side of the road with a vehicle repair. And clean, impeccably clean. He would work all day only to come home and toil endless hours in the yard and garden. Every blade of grass manicured, 50-foot tree limbs sawed to perfection, every trace of leaf and debris on a two acre wooded lot raked. My mom believed he was trying to process the horrors he’d seen in Vietnam by losing himself in these chores. She tried to talk with him about it twice. Both times ended badly.

As a father, he was quite the presence. Stoic, steadfast, and strong are words that come to mind. Strict, yes, but in the sense that he was trying to protect us from something greater, perhaps a secret evil and void around the next corner that only he could see. I always felt his love, felt it in the way he would look, hold, and hug me and my sister. Though we didn’t have many of the in-depth conversations that a son yearns for from his father, I always knew he was there, a guiding presence that would always keep me from harm.

My mother and father divorced when I was six. There are probably many reasons. Lack of communication, misunderstandings, different goals, hopes, dreams brought on by the opposite sex. Perhaps it was the death of my newborn brother Christopher. Only three months old, he struggled to breathe from birth.

One Saturday morning my mother saw that he wasn’t breathing. She called for the ambulance. My dad, refusing to wait, scooped him up and ran out the door and on foot to the ER almost ten miles away. The ambulance caught up to him halfway there. But Christopher had died hours before.

Life for my parents changed that day. How do you recover from something like that? Can you? As a father now, I couldn’t imagine it. Coupled with combat and a failing marriage, the crushing stress must have taken its toll. But John Boy persevered. Moving forward and adapting to the situation is what a Marine does. And that’s exactly what John Boy did. For almost nine years.

They were good years, too. John Boy remarried, hunted, fished, he bought a F150 truck, he worked at Phillip Morris, he spent time with his kids, he spent time with his family. He was a good man, he was the best of men. An undaunted person that worked hard to compartmentalize the pain, put it somewhere safe, and redirect it to someplace far away.

But one bleak January morning, that pain became too much. Maybe he simply couldn’t adapt anymore, maybe the horrors and nightmares of life and war became too great. Maybe he blamed himself for Christopher. Maybe, just maybe, he hoped he’d found a way out from the pain and tragedy.

He took his life like a Marine. A single pistol shot to the heart. Maybe that’s where it hurt most.

“I survived, but it’s not a happy ending.”

― Tim O’Brien, The Things They Carried

(shared by John’s son, Ben)